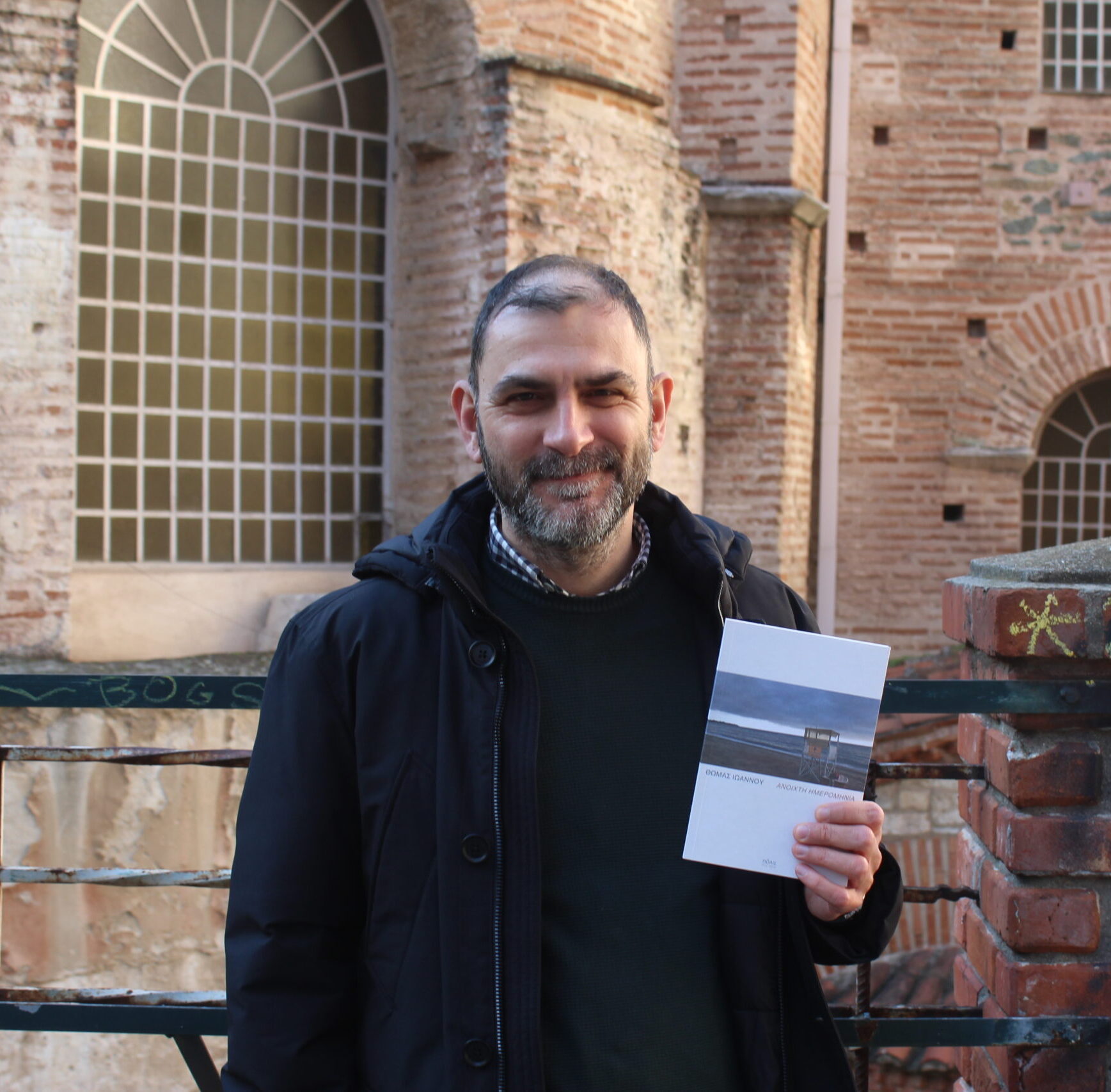

“That’s one of the few areas in Milan that hasn’t been gentrified… yet,” Vincenzo Latronico says to me after greeting me in Isola, a neighborhood not far from the city’s centre. Although Anna and Tom, the protagonists of his best-selling, award-winning book Perfection, embody the modernization of the world as we now know it, Latronico himself was a member of the anti-gentrification movement—before the term was cool—nearly two decades ago, in the exact same area.

He guides me through the place he returned to after spending years in Berlin—the city that inspired his book. He shares his story: a tale of two cities—Milan and Berlin—and of collectivity and individualism, all of which shaped the creative process behind Perfection. Once felt to him “unpublishable,” the book is now a global hit, embraced by thousands who find pieces of themselves in his words. I wholeheartedly thank him for this conversation.

-Can you tell me about the first book you ever read?

-It’s definitely not the first book I read, but it’s the first book that made me feel something really strong was going on. I must have been 15, and before that, I was just reading comic books and playing a lot of video games. And then, because it was referenced in a comic book I liked, I ended up buying a collection of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories, The Tales of Mystery and Imagination. I remember, I spent the whole night reading that book and felt that something was happening.

-I think I read it around 15, too.

– It’s a good age to start with Edgar Allan Poe.

-And you’re also a translator. Which came first?

-By far translation, because my mother was a translator as well and she worked for European institutions. I grew up in Luxembourg, where many languages were already in use.

Somehow, it always came spontaneously to me. During class, when I wasn’t listening to the teacher, I was translating song lyrics or similar things. I started interning at a publishing house through a work program at my school when I was very young, 17.

Then, the publisher acquired a novel by a 19-year-old American writer. They asked me to translate it since I was the same age. Of course, I did a terrible job, really bad. But that is how I started.

-Which book was that?

-It’s called “Twelve” by Nick McDonell.

-That experience marked your leap into writing, correct?

-It took me a few years to admit to myself that I wanted to write. I was very shy about it, so I was just translating for quite a long time.

-You’ve translated Orwell, Oscar Wilde, and Fitzgerald. How has translation influenced your writing as a novelist?

– In a lot of ways. Somehow, when you really enter the tone or the style of a writer, the first pages are very hard. You have to do it several times because you have to think like they think and use the language like they use the language.

Once you get to that point, it goes much more smoothly because you can kind of channel their spirit somehow. Then when you stop, something remains with you, like some ways of using a word or some ways of doing a sentence.

At the beginning, you feel like you’re stealing, like I’m stealing this thing from Fitzgerald. But then after a while, they just kind of stay with you. It’s a metaphor I have already used a couple of times, but I think it’s really precise: you host people at your apartment, and everyone forgets a t-shirt, a hat, or a pair of socks. Then you start using them somehow, and you don’t remember. After a while, it’s just your word.

-But you write in Italian?

-Yeah. I worked as a journalist in English for a while, but I wouldn’t be able to write fiction.

“Even if your English is 98%, literature happens in that 2%, you know?”

-Why do you feel you can’t write fiction in English?

–The idea of style in literature is about choosing between all the possible alternatives,the word, the image, or the rhythm that is the right one for what you want to say. You have to be aware of all of the alternatives. Even if your English is 98%, literature happens in that 2%, you know?

Even my Italian is not as good as I would like it to be, because I keep wanting to learn more words. I might probably write something okay in English if I devoted a lot of effort to it, but I wouldn’t be satisfied. It’s just frustrating because you feel that there are possibilities in the sentence that you don’t see.

-Your first novel was released in 2008, and since then, you have written three more. How do you believe you have evolved as a writer since your first novel?

-My first three novels had a similar tone and content. They were all very political. I have been involved in politics since I was a teenager. My first novel is about the 2001 G8 in Genoa.

At the time, there was the anti-globalization movement, which would organize enormous protests in the cities where the G8 would meet. The biggest that ever happened was in 2001 in Genoa.

Hundreds of thousands of people were coming from all over the world. I was part of the student movement in Italy then, and we all felt that something this big was going to change things. Instead, nothing happened. The police were super violent. They killed an Italian protester who was 20 years old. There were tortures, it was really terrible.

The parents of my generation were part of the 1968 protests. Growing up, you always felt that there was a kind of continuity between politics as it was done in the 60s and in the 70s, and as we did it as well, protesting on the streets, occupying buildings.

The G8 in Genoa in 2001 was the moment in which we saw that this did not work. That even if you get the biggest protest ever, the only thing that happens is that a kid dies.

I’m extremely happy to see that younger generations today are getting back to this kind of big protests, such as against climate change or the genocide in Gaza. Just think: ten years ago, this wasn’t happening.

In the West, there was a significant pause in this kind of street politics, which I think stemmed from the anti-globalization movement’s failure to achieve any tangible results. The novel is about that; it’s set in the week before the G8 in Genoa, amid these preparations, and ends before they go.

But you, as a reader, were supposed to know that then. Yeah, it’s doomed. By the way, have you noticed the skyscrapers with the trees not far from here?

-Yes, I did notice them.

-So that’s funny: there used to be a former industrial building where those skyscrapers rose,which was a squat of which I was part. It’s called “La Stecca degli Artigiani”. It was a community center, but it was illegal, and it had just taken the place. We were volunteering, we had a free after-school, free meals for everybody.

We were at the center of a big fight with the developer and the city to save this space for the neighborhood. We didn’t just want to stay here; maybe they could have made it into something that brought value to the neighborhood. You see what happened now. Skyscrapers. My second novel is about this story.

After we were evicted, arrested, and the building was destroyed, many of us were disappointed. Most people from our collective left Italy.

“I can talk at least for myself, I was a bit disappointed by collective action. So I chose a life of total individualism, the one I write about in Perfection.”

-And you followed?

-We were evicted in 2007. I went to Berlin the next year. I can talk at least for myself, I was a bit disappointed by collective action. So I chose a life of total individualism, the one I write about in “Perfection.” For years, I tried to write and started many books, but I never finished one. I was always frustrated or unhappy with them.

I think it’s because telling a story belongs in a community. You tell your story “from a pulpit to the masses.” You are part of a group, and you tell a story important to that group. The group can be a political group, a neighborhood, anything… That was one of the reasons I wasn’t really able to find the strength or the meaning to write the story; I was also living a very hedonistic, individualistic life back then.

Until I realized that, somehow, the people who felt trapped in this kind of individualistic life, frustrated by it and not really knowing why, were also a community.

-Doesn’t this community read “Perfection”? This is a community of indie books.

-Yes and it’s really magical to see: the book is selling extremely well in English. I get so many messages from people saying, “I feel so seen”. It makes you feel that what you’re doing is worth it.

-I think that the book resonates with many generations, not just millennials. I was born in 2001, so I’m Gen Z. I’ve also read reviews from Gen X, and everyone finds a bit of themselves in “Perfection.”

-I think that this is because instead of focusing on a specific technology, platform, or social media, I wanted to kind of tell the story of how people’s inner life is impacted by digitalization. This is something that, to a certain extent, happens to all generations that have lived through this time. The Germans hated it.

– But Berliners say they’re not Germans, right?

-Yes, they’re one of a kind, Berliners.

“One of the things that led me to write Perfection during the pandemic was that I opened Instagram and realized many things I thought I had come to spontaneously had actually come from there, even though I didn’t have it.”

-You also have many references to social media in the book. Did your social media presence influence the way you write and the way you see the world in general?

-Not only the way I write and see the world, but, I guess, the way I am, something deeper. Think about it. How many ideas have come from something you’ve seen? How many curiosities have you come across that have spread through social media? We all spend hours every day absorbing this content.

It would be absurd to think it doesn’t change you. So this is what, for instance, and it was funny because when I, like, I didn’t have Instagram until the pandemic. One of the things that led me to write “Perfection” during the pandemic was that I opened Instagram and realized many things I thought I had come to spontaneously had actually come from there, even though I didn’t have it.

Like, the plants in the apartment, or some obsession with well-plated dishes — all of this stuff clearly comes from there — but I didn’t have Instagram. So how did I absorb it? Somehow, because these ideas travel. Τhis is one of the things that prompted me to write this book as well.

-But you didn’t have any kind of social media?

-Just Twitter.

-Twitter, okay, but I don’t think these kinds of things travel on Twitter.

-Exactly.

-Maybe just Pinterest.

-I didn’t have that either.

-How do you feel about “Perfection” being a bestseller worldwide, shortlisted for the Booker award, and about all this recognition?

–I didn’t expect it at all. When I finished the book, I was in quite a complicated time in my life, and I sent an email to my agent, in which I said, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, this book is unpublishable. It has no plot. It has no characters. It has no dialogue. Please, let’s try to do something with it, because it’s the only thing I could finish in years.”

-Now that everything is kind of coming, the awards, the messages, the “New York Times”, how does that make you feel?

-A little bit in disbelief. I’m afraid I’m going to wake up at some point. But it feels great. Sometimes I think, “Okay, if I’d known this at 17, they would say my dream is coming true.”

-Let’s go to gentrification, because I believe that the collective you referred to before, was also anti-gentrification. In the book, Anne and Tom were part of it and contributed to it.

–Of course, but nobody wants to see themselves as part of it. We were too: the paradoxical thing, the thing that was most painful to us is that, where the towers are, there used to be this abandoned industrial building, which was just abandoned. People didn’t know this neighbourhood because it was just an ugly area on the outskirts of Milan.

Then we cleaned up the whole place. We started a farmer’s market. We started a bar with a cinema. We started a bike repair shop. We started an after-school program for kids, where parents could come and get a drink. In a way, we started the gentrification!

People wouldn’t have thought that the neighbourhood was cool if we hadn’t been there. That’s truly a paradox. Then, when we started raising awareness in the neighbourhood for what was happening, this was almost 20 years ago, the word “gentrification” wasn’t even known.

It was known to people involved in politics or urban design, but it wasn’t as widespread as it is now. One of the actions that we did was, you know, those stickers that you put in the bathrooms of bars? We made stickers with the word ‘gentrification’ on them, with its definition.

I remember we had a meeting and tried to say, “OK, how do you write it so everybody understands it?” One option that we didn’t use, but that stayed with me because it was so true, was “gentrification is the crime whose name is known only to the guilty.” If you know what it means, you’re doing it. That was the case then.

-What are your thoughts on gentrification today?

-My thought is that we are framing the process in the completely wrong way. We frame it in terms of individuals. The gentrification of this neighborhood is my fault, because I bought an apartment here, or your fault, because you go here for drinks.

This is similar to what the xenophobic right says when they say that joblessness is the fault of the immigrant who takes away your job. Gentrification is not an individual problem. Ιt’s a structural problem. It’s a problem the political system has allowed: a speculative commodity rather than a basic right.

Once housing is a speculative commodity, of course, you will look for the cheapest, nicest house that you can find. This is completely rational; it’s not your fault. The fault lies in the fact that it is legal for you to speculate on a house. I think that Greece also had a golden visa system.

-Yes, it does.

-Take the gentrification of Lisbon, for example: you read the article about the American artist buying a factory in Lisbon for less than a studio apartment in New York and living there, and you say, “this douchebag is gentrifying the city”. He probably is.

But the problem with Lisbon’s gentrification is the golden visa program; it’s not the people who go there. Just like the problem of plastics in the sea. It’s not that you and I do not recycle enough. It’s that plastic bottles should be forbidden.

Ιt’s much easier to put the blame on individuals than to take collective responsibility. That’s why I think that the problem of gentrification is a systemic political problem, not an individual one.

“The city is a technology for bringing people together.”

-Berlin plays a significant role in the book. How have you witnessed its changes in recent years?

-If you read Balzac in the 19th century or Don DeLillo in New York of the 50s and 60s, you know that every Metropolis has always had very cheap areas where students, artists, and small-time criminals coexisted. Ιt was at the heart of the Metropolis. In Balzac, you have these poor students living in these tenement houses. They walk the streets, and there’s a palace of some noblewoman. They all see each other at the opera theatre. This is the essence of the city.

This is why culture flourishes in the city, because there’s a lot of everything. I was able to witness that in Berlin at the time, and that’s why I feel very lucky. This is no longer the case.

Now, at least in the West, cities are uniformly very expensive. This is not just a problem of them being expensive. It’s a problem that denies the role. The city is a technology for bringing people together. We’ve seen that it’s a very good technology because when many different people come together, new ideas emerge. But now this technology no longer works because the people who can come to cities are increasingly the same.

Now I’m in a position to afford a nice apartment in a big city, but I wouldn’t have gotten to this point if cities had been the way they are today. So I don’t know what’s going to happen to your generation, for instance.

I have friends in Milan who are in their 30s. They are professional journalists, they work in publishing, and they live in shared rooms in the periphery. At 30, you should be able to have your own home and a family, you know?

-Yes.

-I don’t know what’s going to happen. Of course, this process happened everywhere. But Berlin was so much cheaper then than now.

-Do you ever miss it?

-Do I miss it? No, I miss my 20s.

-Okay, fair.

-Α friend of mine, who is also a novelist, wrote a book about Berlin. She was interviewed once, and they asked her, “Didn’t Berlin get worse?”. “Of course it got worse. But the other places got even worse.” she answered.

-Anna and Tom seem to have it all, yet they feel incomplete. What is it missing from their perfect lives?

– I think what is missing is that they’re lonely.

-Even with each other.

-They can be happy with each other, but a couple does not exhaust your need for belonging.

“If I had had actual characters, the characters would have had a plot. They would have fought, or had sex, or slept with other people, and this would have become the story, and the rest would have been back to the background. The only way I could make you hear the tiny little noises the background makes is, if nobody was speaking on the stage. “

-This has been a critique of the book, that you don’t really dive into their personalities, and you see them as a whole, the two people.

-That’s deliberate, I know that, I wanted to do that. Of course, one might say, “I don’t like a book that stays so much on the surface”, and that’s completely legitimate. But in my case, I think it’s because the things that I cared about in this book are normally in the background.

They’re like very subtle things: how you decide to arrange your apartment, how you live your life online. These things are the background. They’re never the plot.

If I had had actual characters, the characters would have had a plot. They would have fought, or had sex, or slept with other people, and this would have become the story, and the rest would have been back to the background. The only way I could make you hear the tiny little noises the background makes is, if nobody was speaking on the stage.

-So one might say that it’s a book in which the background is also the protagonist?

-It’s just made of background: either the physical background or the intellectual background of a character, or the emotional background, of the kind of things that normally are written before the story begins.

-What about that scene at the airport, when they see themselves again in the airport’s mirror and witness how much they have changed. Do you find parallels with yourself?

-For me, it was the Bergamo airport. Everything in that book is real. The book is fiction, but everything either happened to me or to my friends. I think that also explains why many people have said that the book is satirical, but I don’t think it’s cruel.

I think it’s gentle towards these characters and that’s because these people are me and my friends.

-I’ll share with you my favourite page. I’ve read it many times. You’re writing : “They would have liked it if they were 20 years old in 1968. Or if they had protested on that day, the Berlin Wall would have fallen. Anna and Tom were not only jealous of those who managed to fight for a radically different world, but even for those who were in the position to imagine it.”

-Yeah, this is me too. Here I’m paraphrasing. Have you read Capitalist Realism by Mark Fisher? That’s exactly what this paragraph is about.

-Do you think that there is hope that our generations won’t be that lost?

-Lol, no. No, no, no. I don’t know.

-Don’t you feel like we can find a purpose, collectively?

-I have been part of a commune in France for about two years, a few years back. It worked. It’s a really incredible place where you feel like you’re in a different world, and you are. On that scale, I think these things are possible.

On a bigger scale, I don’t know. It doesn’t sound like the best age for that.

“I didn’t realize it when I was writing, but I wrote the book in the window as that age of innocence was ending.”

-Do you think that “Perfection” can work as a historical artifact for future generations, of how millennials were?

– I would hope that. Of course, it’s very arrogant to think that you’re writing for the future. But at the same time, this is also what novels do. If you want to know what the 19th century was like, you read a history book. If you want to know what it feels like to wake up, how people go to the bathroom in the 19th century, you read Dostoevsky, you read Jane Austen. Novels tell you the grain of everyday life.

I tried to do that as well. I didn’t realize it when I was writing, but I wrote the book in the window as that age of innocence was ending. During the pandemic, just before the invasion of Ukraine, a little bit before the genocide in Gaza, and the absolute fascist turn of the tech industry. These things together really determined a transformation of the Zeitgeist.

You were too young, but Google’s first slogan was “Don’t be evil.” We believed it then. The first slogan of Airbnb was “travel like a human”. I remember the first time I used Airbnb —it was a dream. I could travel much, much cheaper than a hotel. I was at someone’s apartment, met them, and they told me where to go in the city. This felt human. The world was improving.

One of the subtexts of this book is that this was a time when people sincerely felt, maybe because they had been misled, because they were naive, because we were naive, that technology was changing the world for the better.

Now it’s grotesque to say, but the discourse in 2010 was not about how Californian startup culture was bringing about fascism. It was about how it was a child of the counterculture.

-We had romanticized it.

-In retrospect, that was an age of innocence for Europeans, especially. The world has changed so drastically, and exactly while I was writing it, that I didn’t realize that I was writing the document of a time that had ended. But I was.

-So, since our readers are mainly students and young people, what would you advise a young person who dreams of being a writer?

-I think that writing is not about writing. Writing is about looking. Or listening. In many ways, writing is a much poorer medium than, for instance, photography. I can take a photograph of this, and it has everything.The color of the cars, the kind of trees, and your position.

If I were to describe it, I could spend 50 pages and not capture every detail that would be in a picture. So, when you write, you have to choose.You have to look and say, “Okay, this one detail, this one thing is what is most important.” This poverty — let’s say, the fact that you have much less information to go on — is the same way attention works: it goes from one detail to the next.

You can’t remember everything you see. You remember a couple of things. I think that good writing follows the process of attention. For me, it is about being very attentive to the world or to some things in the world.

I didn’t put dialogue in the book because I’m terrible at dialogue. I don’t remember how people talk. But I remember the details. I think that’s more important.

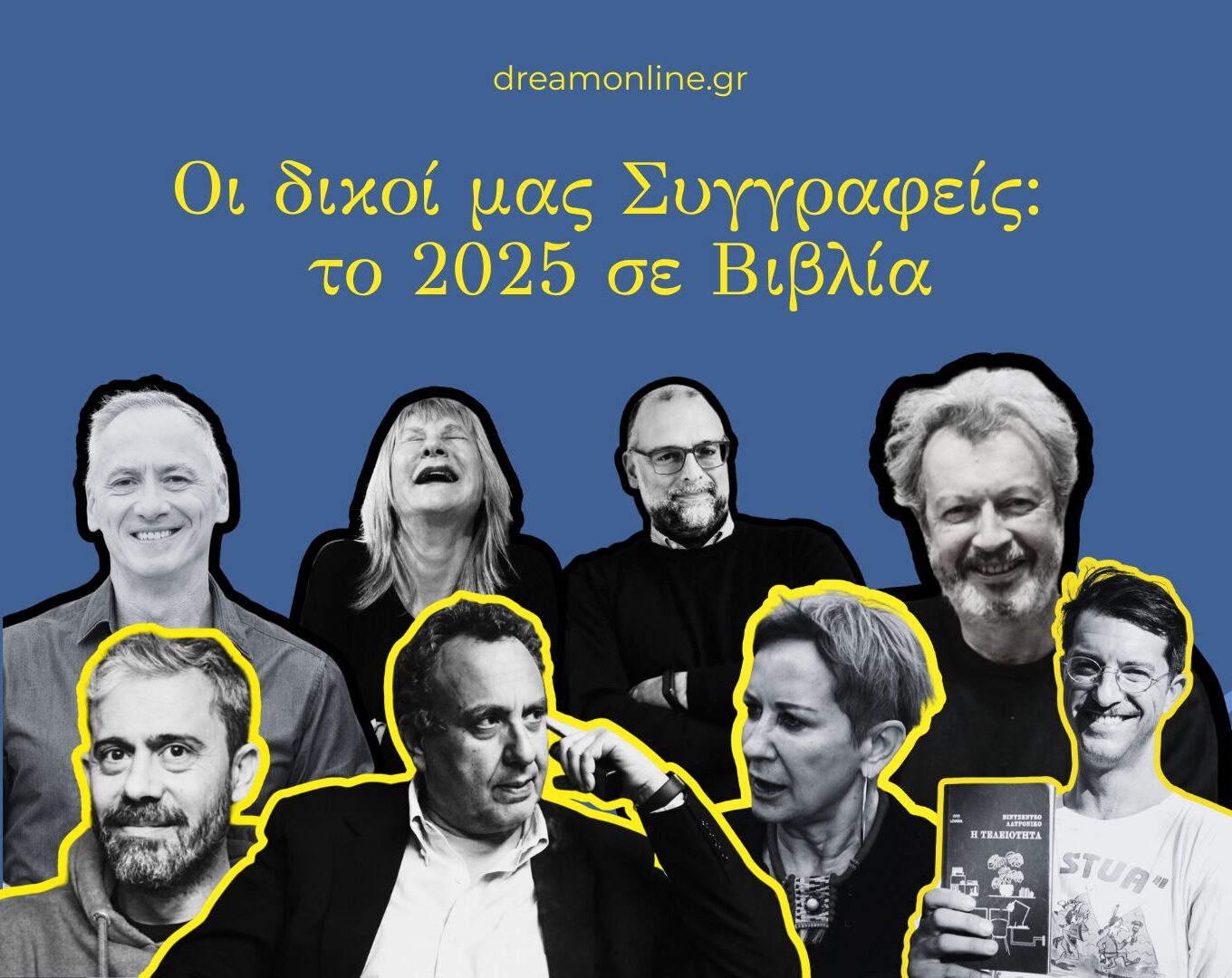

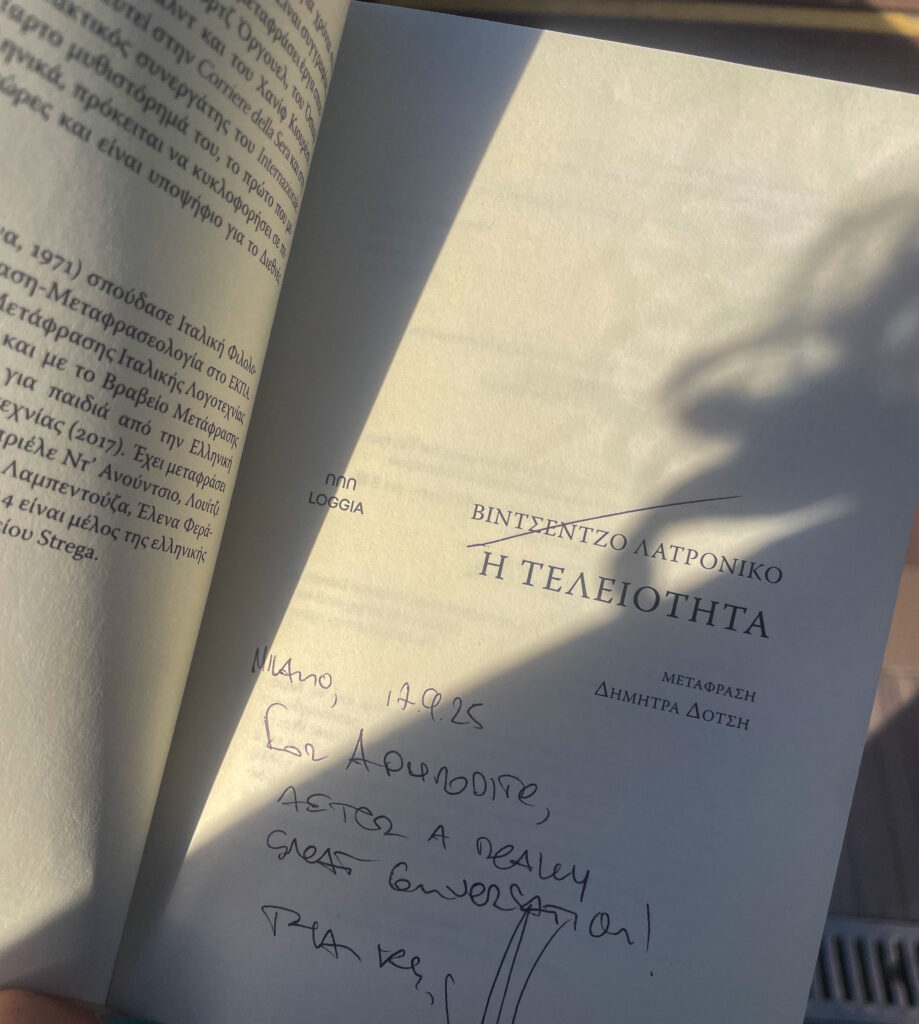

“Perfection” is available in Greek via Loggia publications.

Interview: Aphrodite Kerameos